Why Asking the Right Questions Always Leads to Improvement

November 29, 2017

Written By:

Joe Dyer | President

I am the proud father of two little boys, ages three and five. Among the busy days, messes, and laughter there is one other constant: questions. What are we doing tonight? How does a key work? Could you somehow get inside a leaf? Maybe you can relate to this line of questioning. Recently my son asked, “Dad, where do clouds come from?” I explained the water cycle, how water vapor comes from lakes and the sea, and how the clouds form. He followed up, “Then why do clouds have rain?” Explanation. “Then how does water stay in the lakes if it is always leaving to form clouds?” Explanation. Question. Repeat. Children remind us every day that the capacity to question is powerful.

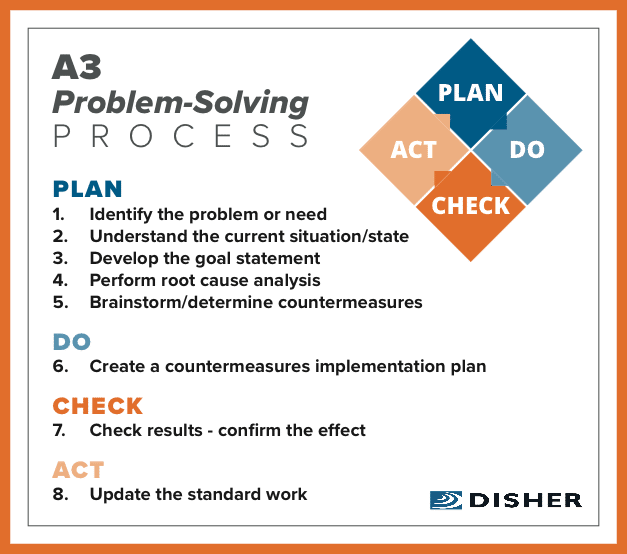

A similar sequence of thought can lead to massive success in engineering, manufacturing, and design when properly controlled. When we don’t readily know the answer, (which is often the case in scientific fields such as engineering), the process goes more like this: observe, question, experiment, analyze/explain, repeat. Maybe you have heard this referred to as: the scientific method; the plan-do-check-adjust (PDCA) cycle; the define, measure, analyze, improve; or the control (DMAIC) process. The semantics of it all can be stripped away to its solid core – being skilled at inquiry.

The Skill of Inquiry

Anthropologist Claude Levi-Strauss put it well, “The wise man doesn’t give the right answers, he poses the right questions.” In our modern society, we are obsessed with knowledge. We ask Google, Alexa, or even the digital assistant on our phones to get instant answers. We have the majority of human knowledge right in our pocket. Because of this, we are losing the ability to think critically, ask questions, and be curious. The ability to ask the right questions at the right time defines being skilled at inquiry.

Being skilled at inquiry is not as simple as it sounds. Asking the right questions at the wrong time could be viewed as premature, behind the curve, or socially clumsy. Asking the wrong questions at a crucial moment could derail someone’s thoughts and hinder progress toward the goal of deeper understanding. Perhaps the most naïve of all, some people ask irrelevant questions at unconnected times. Yes, I am talking about children. This is an endearing trait for a child, but this pattern of inquiry coming from a professional problem solver (engineers for instance) is a hindrance.

The skill of inquiry is valuable. It can be applied to anything— any business, any process, any product, and any field for significant outcomes. To design an innovative product, make improvements to a process, change the direction of a business, increase sales, reduce costs, and make more widgets— we need to up our game. How does one become skilled at inquiry?

How to Boost Your Inquiry Skills

1. Curiosity.

A good place to start is where all children start— curiosity. In my last blog post, A Day in the Life of a Manufacturing Engineer, I tell the story of removing a line of CNC code that saved a company close to $100K per year. The success of that line being removed wasn’t because I had vision or metric goal to save $100K per year. That wasn’t the “Why” driving my actions. The true reason was my natural curiosity. I dug down and asked question after question about why that line of code was there until I found the answer. The purpose for why it was originally put there no longer applied, so I removed it. If I did not intentionally develop my inquiry skills, I may have never achieved the bottom-line savings for my customer. If I was content with receiving pat answers, (“The code has always been there”), I would never have kept asking questions. Cultivate your curiosity. Read books outside your field. Talk to people vastly different from you. Ask lots and lots of questions. Strive to always see the bigger picture and your place in it.

2. Time.

Curiosity is key, but time is also critical. Take time to think, notice, and wonder. Kids have curiosity and time— hence all of their probing questions. When was the last time you set aside time to reflect? As an engineer, I operate in many faced-paced environments. I understand how difficult it is to set aside time. But if we are to make this word a better place (by improving processes, products, people, etc.) then we need to make time to reflect. Allowing our minds to have closed loop feedback will refine our thoughts and actions. As a result, we gain a clearer sense of the right questions we should be asking, not necessarily the right answer to those questions.

3. Asking the right questions at the right time.

When curiosity and time are enriched, it teaches us to ask the right questions at the right times. As a manufacturing engineer, I am constantly faced with hitting key metrics like quality, on-time delivery, and cycle time. Some of these goals even compete at times. Regardless, one fact is always at the front of my mind: I do not know everything. If I make a decision on a process issue, it may affect any number of downstream indicators, some of which I can predict and some of which I cannot. I can, however, ask good questions at the proper moment. Why does this cycle time need to be at this level? Why not slower? Why not faster? What is the Takt time? Will quality be affected by this decision? How do I know? What is the specification? What is the validation testing? What is the value add to this process? Who is the customer? Are they internal or external? How is the product being used? What is the design intent and will I be affecting that? You get the point. Answers to these questions sometimes are simple and clean cut. Other questions may need more questions or some experimentation. While others may need a whole department to work on them. Asking the right questions at the right time always drives the best actions.

Let me illustrate this further with a real-world example. Years ago, I was helping to develop an operation in a plant. The process I was working on was one of the key value-add steps in the entire value stream. I began to ask questions to better define my current situation in the bigger picture. Because of that practice, I realized that if this operation was to be successful it needed better material flow into and out of the cell. We might even need to rearrange the floor layout so the next step in the value stream could utilize product first in-first out (FIFO) coming from the process I was working on. I started asking some questions. Why is the cell laid out this way? What are all the variations of these parts? How is material moving? I decided I needed to see the current value stream map or overall process flow diagram. I asked a manager. No response. I asked that manager’s manager in person. I was on to something and needed to know more. He responded, “Why do you need that?” A fair question. I explained the situation and the questions I had, and I offered some potential improvements. His response? “Stay on the task at hand and don’t ask those bigger-picture questions.” Ouch. My kindling fire of improvement was just doused with water.

This example, although it could have been handled better, illustrates clearly that we should be encouraging our teams in their questioning. We should also watch our responses as recipients to some of those questions. If you and your teams are truly developing effective inquiry skills then the right questions at the right time will always lead to improvement. Questions are nothing to be afraid of. An engineer or “professional problem solver” properly armed with the skill of inquiry can be a catalyst for great discovery and progress.

There are many problem-solving techniques and methods that can help your organization quantify, formalize, and capture all of the questions and improvements related to a project. Thankfully, you don’t need to figure it out alone. Several of these tools like Kepner-Tragoe, 8D, 5 Why, Fishbone diagrams, (the list goes on), are firmly in the DISHER toolbelt and routinely leveraged by our experienced engineering team. We apply the skill of inquiry to frequently crossover the artificial barriers of engineering titles to do what we do best: solve problems! Let us know how we can help with your next project.

Written By: Joe Dyer, Team Lead – Manufacturing Tech Services

Joe has an Aeronautical Engineering degree from Western Michigan. He has a variety of experiences in manufacturing, quality systems, machining, and programming. Joe likes to spend time at home with his wife and two boys and lead ministries at his church.